Jack Hanna

Canada’s Picasso spent his life in the Arctic and never had an art lesson.

Nick Sikkuark, entirely self-taught, worked in many mediums: sculpture, painting, drawing, caricature, and illustrated children’s books. Like Picasso, he was a genius in all of them. He died in 2013 at the age 70.

The first major exhibition of his work is a short walking distance from Centretown at the National Gallery of Canada. It is entitled Humour and Horror. It lives up to the title.

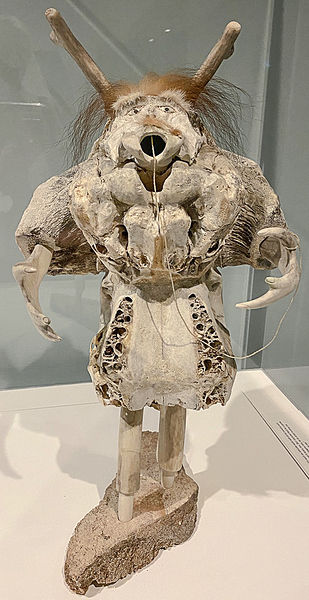

“I carve from my imagination – shamans and devil spirits, things no one would imagine,” Sikkuark once told an interviewer. “When I carve them, I make them live.”

His art is fantastic, but exudes humanity. Look at a Sikkuark carving and there is curiosity – what is this? – but that quickly morphs into empathy for the engaging face.

“I like to make faces funny or ugly,” Sikkuark said, “so people will look into the details and wonder what I have carved, to see and be puzzled… The scarier the better.”

Sikkuark’s work clearly is Inuit art. He worked in soapstone, bone, antler, tusk, and fur, as well as with paints and pencils.

But this is not like any art you’ve seen before.

Sikkuark’s works captivate because the viewer experiences a combination of emotions. A face is fanciful, even macabre, but there is realism that grabs a viewer’s sensibilities.

“You see gnashing teeth, or eyes bulging or closed in pain, and you instinctively want to step back,” says Christine Lalonde, curator of the exhibition. “But the closer you get, the longer you look, whatever emotion enticed you to get close, the opposite emotion seeps in.

“You are just about to laugh at the precariousness of a figure and its circumstances, and then you become empathetic and appreciate how difficult it is to transform from a human into an animal.”

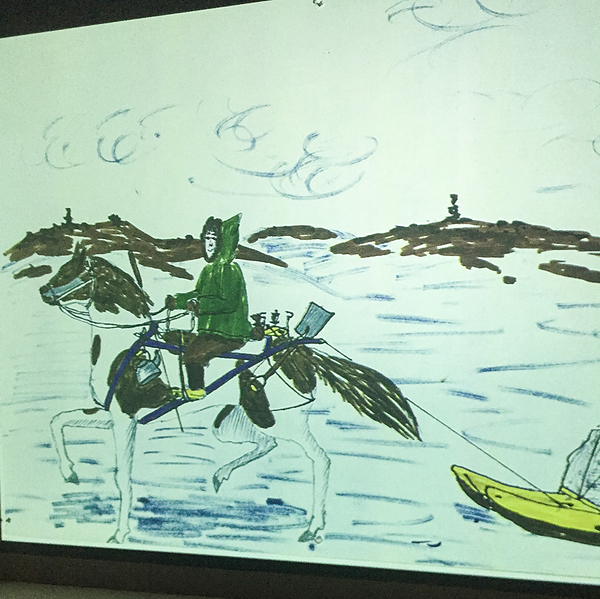

Sikkuark explored many themes: relationships between humans and nature; shamans; Inuit myths and customs; and human transformations into animals or spirits.

But at its heart, his art is about being human. Sculpted faces show pain or struggle, or open-mouthed awe or horror. Although fantastic, they elicit sympathy.

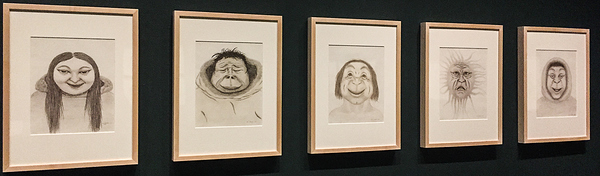

The exhibition includes dozens of monochrome caricatures of people, all of them beguiling because the subject’s humanity leaps off the paper.

Sikkuark was born into an Inuit family that wintered on the land. When he was seven, a German measles epidemic took both his parents. He was raised by relatives and then a priest.

As a child and teenager, he dabbled with drawing and carving but never thought it would be his calling.

He wanted to be a priest. At 18 he left the north to study at a seminary in Winnipeg and in Ottawa.

But Sikkuark found the priesthood was not for him and returned to the north. He married and had a family. He worked in construction and as a hunter and carver. His family lived in several communities, eventually settling in Kugaaruk, on the Arctic coast opposite Baffin Island.

His break came in 1973 when he was commissioned to produce illustrated books for the Northwest Territories Department of Education. He wrote five such books, including Nick Sikkuark’s Book of Things You Will Never See and What Animals Think.

He won a prestigious commission to create the Queen’s Baton for the 1978 Commonwealth Games of carved narwhal tusk and gold.

He became known among aficionados of Inuit art and in the North.

“I want to make people think,” Sikkuark said. “What is that? What does it mean?”

Sikkuark’s works draw forth a mix of emotions. Opposites combine, for instance horror and humour, as the exhibition’s title suggests.

“We find that they are not separate; they are one and the same,” says Lalonde. “Even in sorrow, we feel joy.

“That is his humanity. That is what grabs and holds.”

See Humour and Horror soon. The exhibition ends March 24. Admission is free on Thursdays from 5 to 8 p.m.