Ryan Lythall

I hate to state the obvious, but it’s been a hot summer.

As I type this, it’s 33 degrees Celsius, with a humidex of 41. Thankfully, I have the air conditioner on.

Having air conditioning is often viewed as a luxury, especially for recipients of the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP), seniors, and residents of apartments and long-term care homes without AC.

In 2020, Premier Doug Ford promised that all rooms in long-term care residences would have AC. As of July 20, 90 long-term care homes were still without AC.

Over the past few weeks, we’ve heard stories on how it’s impacting the residents, many with ongoing medical conditions.

However, little has been said about the staff working in LTC homes not equipped with AC. Given we are experiencing a severe shortage of healthcare workers in Ontario, all measures should be taken to ensure that staff and residents are safe and comfortable. The last thing we need right now is to send people to the hospital due to a situation that could have easily been avoided. As well, with fewer personal support workers (PSWs), it becomes more difficult for people with disabilities and seniors to go outside to get cool.

Many ODSP recipients simply cannot afford an AC in their homes. While there are various programs to ease the cost, with prices continually rising those programs fall short of covering the total amount.

Each month, ODSP recipients already have difficult decisions to make. Many must decide between putting food on their table, paying their rent, or paying their hydro bill. Even without using AC, hydro is extremely expensive.

To those living in Centretown, the struggle can be even more challenging.

Recently, I learned for the first time about the Urban Heat Island Effect. Here’s an explanation from the City Of Ottawa’s website.

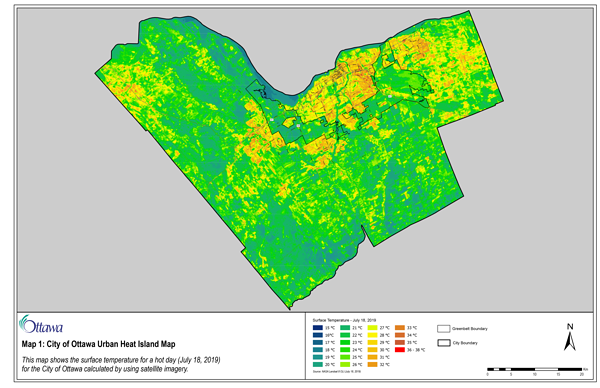

The urban heat island effect occurs when built-up areas are hotter than surrounding areas. Buildings, parking lots and other dark surfaces in built-up areas retain heat and become hotter than nearby greenspaces, water and rural areas. The annual mean air temperature of a city with one million people or more can be one to three degrees Celsius warmer than its surroundings during the day. The difference can be as high as 12 degrees Celsius in the evening.

More information on the Urban Heat Island Effect, complete with coloured maps indicating varying degrees of temperatures, is at engage.ottawa.ca/climate-resiliency/news_feed/urban-heat-island

I’ve lived in Centretown for almost 30 years. I noticed Centretown seemed hotter than other parts of the city, but I never knew why or if it was just my imagination.

For the longest time, I had doubts that climate change was real. Over the last few years, and especially now, it’s pretty clear we’re in a crisis.

We need to do more not only to protect our planet but also our vulnerable residents in Centretown and beyond. When it gets extremely hot or frigid outside, check in on your neighbours, especially if they’re elderly or have a physical disability.

So many of us take for granted that we have AC or can step outside to get fresh air. That’s not always the case, though. Some are stuck at home or in their room simply because there’s no one around to take them out.

Follow Ryan on Twitter: @rolling_enigma

1 comment for “The Good, the Bad, and the Bumpy: Who is most affected by the Centretown heat island?”